Difference-in-Difference in Evaluation

Difference-in-Difference in Evaluation

In my last blog, I discussed how quasi-experimental research designs could elevate program evaluation despite the lack of random assignment. Here I want to share a statistical technique that will transform data from your quasi-experimental design into robust evidence that will help you demonstrate the impact of your program.

Difference-in-difference is a statistical analysis method that examines the differences between two variables depending on the score of a third variable. Difference-in-difference analysis evaluates the impact of an intervention by comparing gains in the outcome variable (e.g., from pre to post intervention) between the treatment and comparison groups (Somers et al., 2013).

In this blog I want to break down difference-in-difference into the main effects which leave the analysis vulnerable to alternative explanations of the findings, and then discuss how difference-in-difference analysis can control for these alternative explanations and provide evidence that indeed your program is leading the impact.

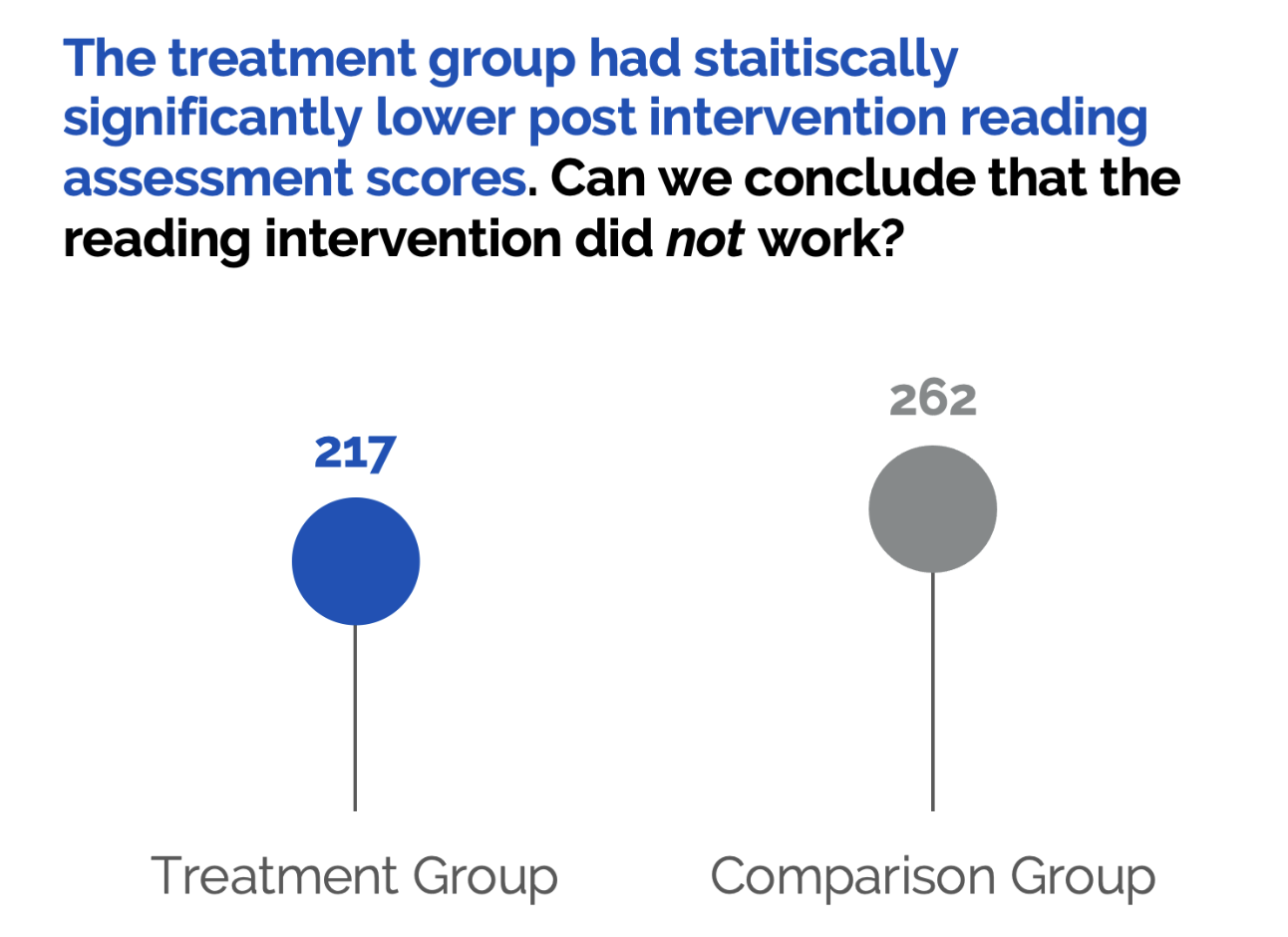

Let us return to the reading intervention example from my previous blog. Let’s say you want to use a standardized reading assessment to evaluate the impact of your reading intervention with kindergarten students1. You could use a simple t-test to compare your treatment groups’ (those who received the reading intervention) reading assessment scores with the comparison groups’ (the students who only got the normal reading lessons) scores to see if those in the treatment group had higher reading assessment scores than the comparison group following the intervention.

Let’s say you found that the treatment group had lower reading assessment scores after the reading intervention compared to the comparison group. Would it be right to conclude that the reading intervention didn’t work?

What if only the students who were struggling to read were given the intervention and the comparison group had higher test scores than the treatment group prior to the reading intervention study? Even with an intervention, the treatment group might still have lower reading assessment scores compared to the comparison group because the treatment group’s reading abilities were so much lower to begin with. We need to be able to compare the pre and post reading assessment scores for the treatment group to understand how the treatment group’s reading abilities changed over time.

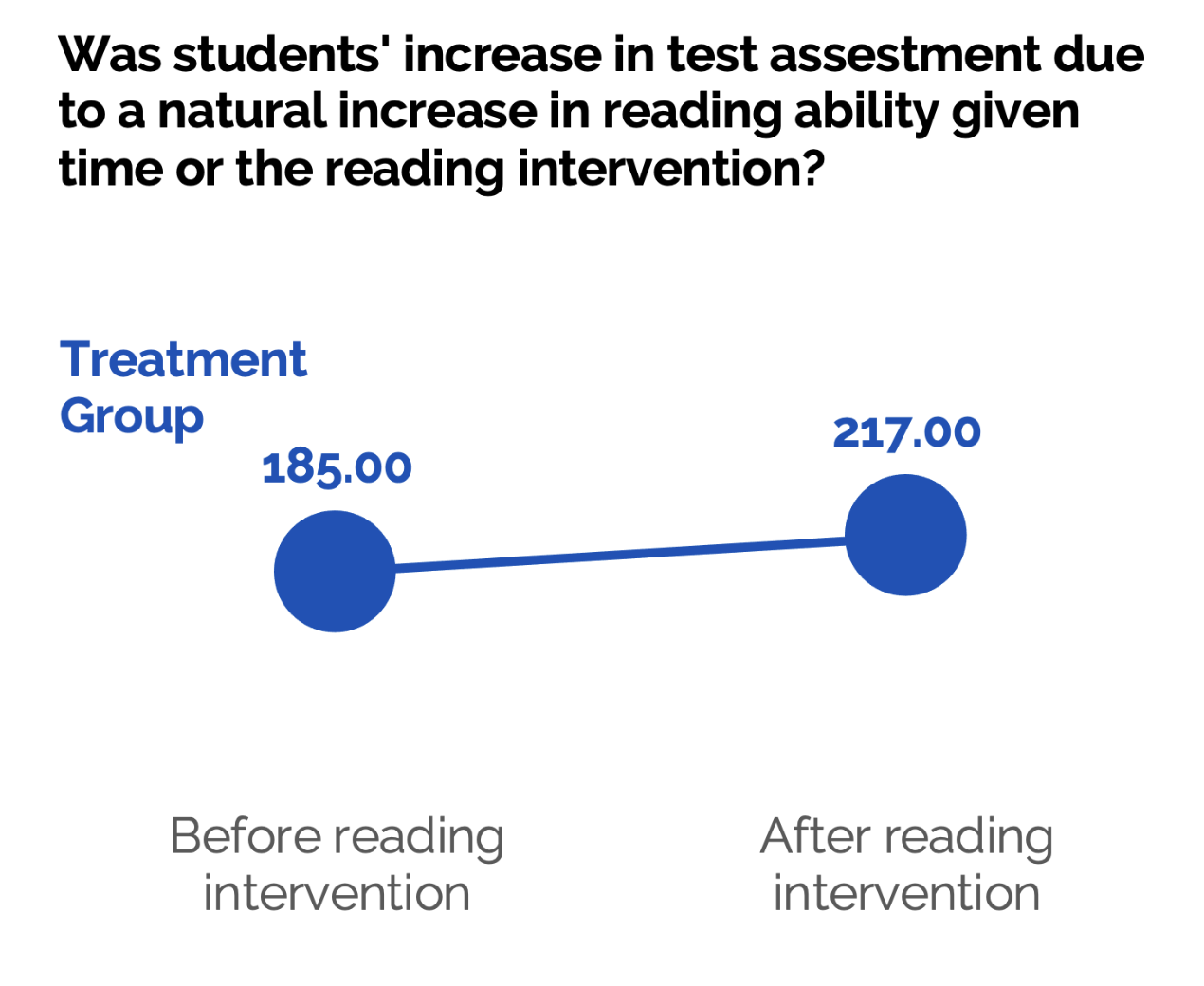

You could compare your treatment groups’ test scores before and after the intervention using a t-test. Let’s say that you find a statistically significant improvement in reading assessment scores from pre to post intervention for your treatment group.

However, if you only look at the main effect of time, it’s hard to know if the gain in test score occurred because of your intervention or because naturally we would expect students’ reading ability to increase overtime. This leaves us with the possibility that an alternative variable (in this case normal classroom reading lessons) is causing the change, and not the reading intervention itself.

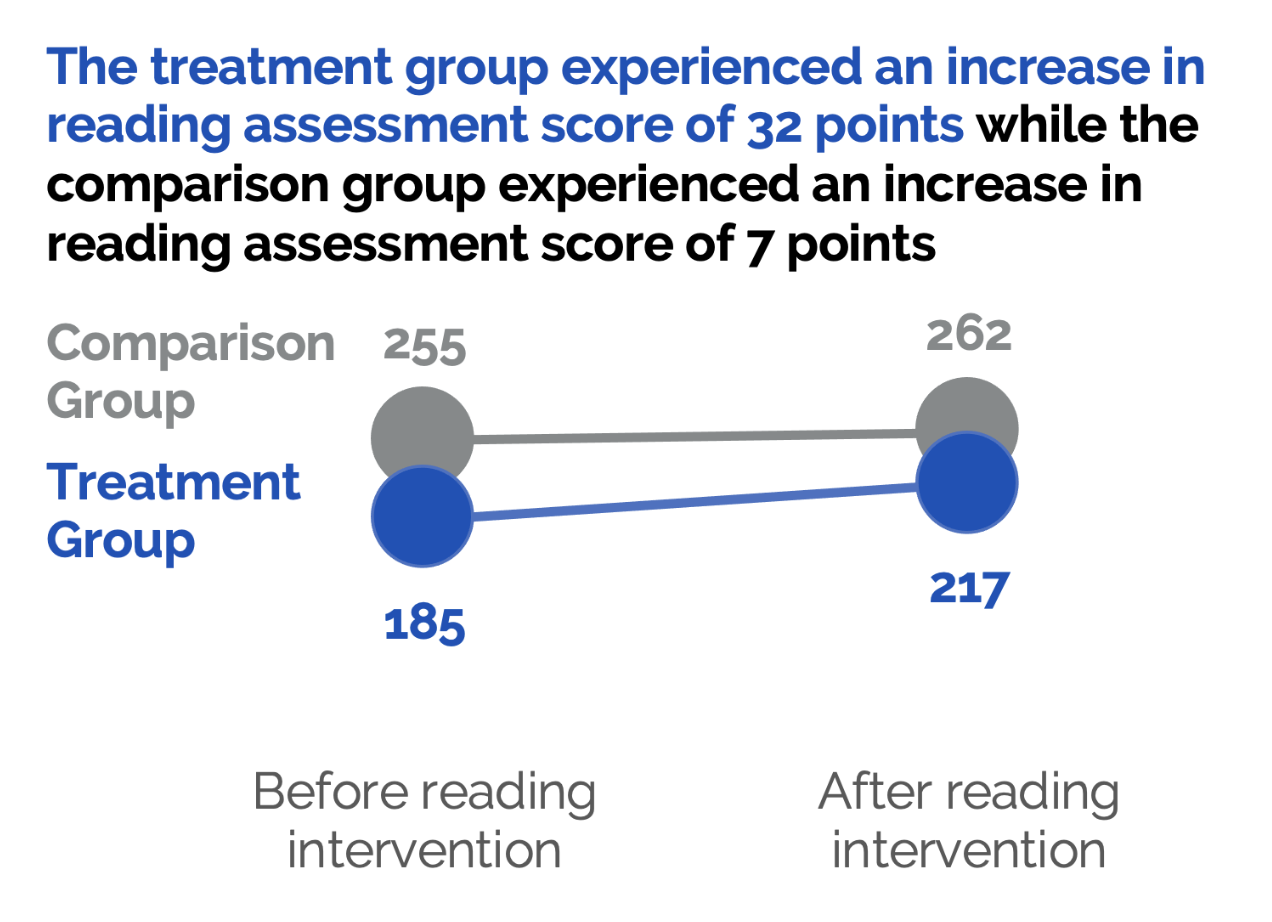

Difference-in-difference allows us to combine these two analyses and compare both time and group effects using interaction terms. Using this technique we can control for the natural increase in reading ability by comparing the comparison and treatment groups, and we can control for differences in reading ability between the two groups by examining the before and after intervention assessment scores for both groups.

Let’s say using difference-in-difference we find that while both groups experience a statistically significant increase in reading from pre to post intervention, the gain is bigger for our treatment group. Based on the increase in reading ability for our comparison group we would expect a slight increase in reading ability due to normal classroom reading lessons, but this alone wouldn’t explain the bigger increase in reading assessment score for our treatment group. Difference-in-difference analysis does rely on the assumption that both our groups are on a similar trajectory in reading assessment scores (i.e., assumes that we would expect to see natural gains in reading for both groups overtime rather than an increase in reading ability for one group and a decrease in reading ability for the other) and that no other extraneous variable is affecting one group more than the other. If we can reasonably assume that the only other difference between our treatment and comparison group is the intervention, we can conclude with strong evidence that the reading intervention program has an impact on reading assessment scores and leads to improved reading outcomes for program recipients.

Difference-in-difference isn’t the only statistical method that can be used to provide strong evidence regarding the impact of a program, other statistical techniques that can be used for non-experimental designs include propensity score matching, regression discontinuity, and comparative interrupted times series designs (Fredriksson et al., 2019; Somers et al., 2013). Consulting with a local evaluator can help you find the appropriate statistical techniques to match your needs and evaluate the impact of your program.

1 All data in this blog post are fictional and for example purposes only.

Contributed By Sabrina Gregersen

Sabrina Gregersen is an Associate Researcher for the Research, Evaluation & Dissemination Department at the Center for Educational Opportunity Programs. She currently manages the data collection processes and conducts the formative and summative evaluations of several of CEOP’s federally funded college access programs, including GEAR UP.

Follow @CEOPmedia on Twitter to learn more about how our Research, Evaluation, and Dissemination team leverages data and strategic dissemination to improve program outcomes while improving the visibility of college access programs.