Using Quasi-Experimental Designs in Evaluation

Using Quasi-Experimental Designs in Evaluation

Most practitioners we work with want to know, “Did my program produce my desired outcome?” Although this question appears to be straight forward and easy to answer, the methods you would need to apply to fully address the question are quite nuanced. The gold standard of research would suggest that you need to conduct a full randomized experimental design to infer causation and answer the question of whether it was your intervention that produced the results. Unfortunately, conducting an experimental research design in an evaluation setting can be a challenge for many reasons. For one, in most cases it’s not ethical or even possible to randomly assign people into groups for evaluation purposes.

So, what’s the alternative? How can we provide evidence that a specific program or intervention is working? While true random experimental research designs are the best approach to inferring causation, quasi-experimental research can provide strong evidence that a treatment or intervention is indeed effective. Although quasi-experimental designs (QED) do not randomly assign people into groups, evaluators can use statistical methods to explore possible causes.

To illustrate how a QED study works let’s look at an example. Let’s say you want to implement a new reading intervention in your kindergarten classroom. You want to know if this new reading curriculum better prepares your students for independent reading compared to the standard curriculum you’ve been using for years. Because you do not have the ability to randomly assign your kids to a classroom or to the school they attend (e.g., kindergarteners are placed in this grade based on age, and families may have a multitude of reasons for choosing a particular school), it’s difficult for you to truly understand if the intervention led to an increase in independent reading or if other external student characteristics (e.g., the student reads every night at home with their parent) led to the change.

To help you figure out the impact of your reading intervention you could partner with a local evaluator to conduct a QED. Let’s explore some examples of how an evaluator might design a QED study for your kindergarten reading intervention.

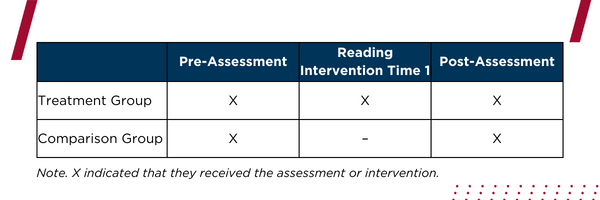

QED Option 1

In a strong QED, evaluators would assign the reading intervention (the treatment group) to kindergarten classes A, D, and E and give kindergarten classes B, C, and F the standard curriculum (the comparison group). Next evaluators would create a pre- and post-assessment that would be administered before and after the new reading intervention. Evaluators would then use statistical methods to examine differences from the pre- to post-intervention for both groups to explore the impact of your reading intervention on independent reading levels.

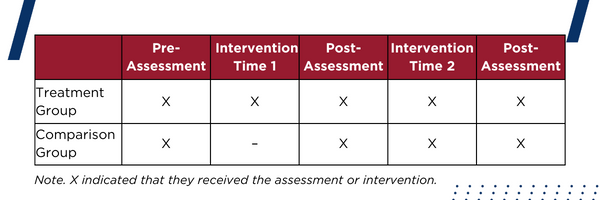

QED Option 2

In some instances, you may want all students to benefit from the reading intervention. In this scenario, your local evaluator would give the reading intervention to the treatment group in the first half of the school year while only giving the comparison group the standard curriculum. Following a post-assessment, they would then give the intervention to the comparison group in the second half of the school year. This would still provide the evaluator with pre- and post-assessment data for statistical analysis, while both groups would benefit from the reading intervention.

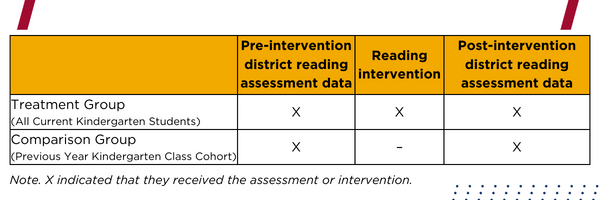

QED Option 3

Next, let’s imagine in our example above that the superintendent said that all kindergarteners in the school district will receive the reading intervention for the whole year. In this case, your local evaluator could use the previous year’s kindergarten class as a comparison group. Because it is not possible to go back in time to give last year’s kindergarten students the pre- and post-assessment, the evaluator may need to use other required reading assessment data from the school district to compare with the new kindergarten class.

While QEDs cannot account for all the possible external characteristics that may lead to changes on the outcome of interest, with careful planning this evaluation approach can provide strong evidence that your interventions are effective.

Contributed By Sabrina Gregersen

Sabrina Gregersen is an Associate Researcher for the Research, Evaluation & Dissemination Department at the Center for Educational Opportunity Programs. She currently manages the data collection processes and conducts the formative and summative evaluations of several of CEOP’s federally funded college access programs, including GEAR UP.

Follow @CEOPmedia on Twitter to learn more about how our Research, Evaluation, and Dissemination team leverages data and strategic dissemination to improve program outcomes while improving the visibility of college access programs.